I watched Peter Sellers’ Being There last night for the first time in many, many years. Thoroughly enjoyed it. I saw that the source novel’s author, Jerzy Kosinski, co-wrote the script. I must admit that I haven’t read the book. But watching the film gave me many of the pleasures of reading a finely textured novel, and I came away with the impression that the film probably hewed very closely to the book. Peter Sellers’ performance is extraordinary; given minimal dialogue, he invites the viewer to understand Chauncy Gardiner/Chance the gardener almost entirely through his facial expressions and body language, much the same way Chaplin did fifty and sixty years earlier. The book’s setting in New York was changed in the film to Washington, DC, which I can only think was an improvement, given the liveliness and visual humor of those scenes where Chance emerges for the first time ever from his benefactor’s Washington mansion in a rundown neighborhood not far from the White House and the Capitol Building. I’m very curious now to read the novel and see what other changes were made, if any, and how significant those changes were.

As a pre-teen I read Michael Crichton’s The Andromeda Strain right after seeing the 1971 film version on TV. I was struck by how faithful the film version was to the novel, virtually scene for scene, dialogue line for dialogue line. The only major difference between book and film was the gender of Dr. Leavitt (Peter Leavitt in the book, Ruth Leavitt in the film). The screenwriter, Nelson Gidding, specialized in bringing literary adaptations to both the big and small screens. I was very interested to learn that he also wrote the screenplay for the 1963 film version of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, The Haunting, which I recall also hewed extremely closely to its source material (unlike the rather baleful 1999 remake, which relied far too heavily on CGI effects and not nearly enough on suggestion). Apparently Gidding was a screenwriter who believed that fidelity between source novel and script served a film the best. Given my reactions to The Andromeda Strain and The Haunting, very different films yet both (to me) greatly satisfying cinematic experiences, I’d say he was right — concerning these two projects, at least.

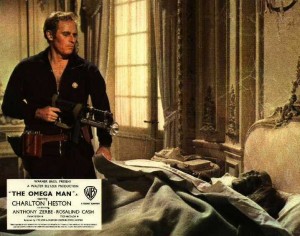

One of my favorite horror/science fiction novels, Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend, has been filmed three times: as The Last Man on Earth (1964) with Vincent Price, The Omega Man (1971) with Charleton Heston, and most recently as I Am Legend (2007) with Will Smith. I haven’t seen the latest version, although I’ve viewed the first two multiple times (The Omega Man regularly scared me silly as a kid when it showed up on network television). Of the three, only the earliest, The Last Man on Earth, was faithful to Matheson’s vision of a virus from outer space killing the great majority of humanity and transforming virtually all the survivors into vampires. Cinematically, however, it is the weakest of the three, having by far the lowest budget and being somewhat hamstrung by Vincent Price’s limp portrayal of protagonist Robert Neville (I’ve read that Will Smith’s performance as Neville was the best thing about I Am Legend, and I’m a big fan of Charleton Heston’s stiff-chinned, bitterly sarcastic, Ford convertible-driving character in The Omega Man). Given the vampire craze of the past quarter century, it really surprises me that no one has attempted a faithful adaptation of Matheson’s scientific updating of the vampire legend since 1964. None of the three films brought to the screen the psychologically devastating twist ending of the novel, when Neville realizes that, in this world of a completely changed humanity, he is the monster, not the beings who have been trying to rid themselves of him.

Another Will Smith genre film, the extremely loose adaptation of Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot, seemed to have little in common with Asimov’s series of linked stories other than a title. Much of the thumbs-down reaction from the SF community was based on the filmmakers’ seeming disregard for their (much beloved and revered) source material. In fact, the screenplay, first entitled Hardwired, originally had no connection with Asimov’s works at all. But when 20th Century Fox acquired the rights from Disney, the new producers dictated the title change and that Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics and some of his character names from the I, Robot stories be shoehorned into the script. Would the picture have been a better film had it been a more faithful adaptation? For a contrafactual look at what might have been, see Harlan Ellison’s screenplay for I, Robot, originally written for Warner Brothers with Asimov’s support.

At the other end of the fidelity scale, Zack Snyder’s 2009 adaptation of Alan Moore’s classic graphic novel Watchmen may have suffered from being too faithful to its source material, at least during its first three quarters. (Some fans of the graphic novel castigated the filmmakers for changing key elements of the novel’s ending; I think the filmmakers made the right choice, as the novel’s climax, featuring a gigantic, dead B.E.M. in midtown Manhattan, could have come across as inappropriately comical on the big screen.) Having read the graphic novel four or five times, I could see, watching the film, how Snyder had utilized artist Dave Gibbons’ page-by-page panels as a storyboard for nearly the entire movie. For the opening scenes involving the murder of the Comedian, this worked very well. For other, more character-focused scenes (the entire romance between the second Silk Spectre and the second Nite Owl), it hardly worked at all. Scenes evocatively and precisely drawn on the page by Gibbons simply did not transfer well to their on-screen miming by Patrick Wilson and Malin Akerman. Had the screenwriters been free to break loose from Moore’s graphic novel dialogue and Gibbons’ scene setting, maybe they could have conjured a more convincing emotional spark between Silk Spectre and Nite Owl. Or maybe not. Maybe Wilson and Akerman just lacked chemistry, and no scriptwriter, no matter how talented, could have given them dialogue that would have allowed them to click. Another contrafactual…

An example of a genre novel adaptation which I think was made a good deal better than it otherwise would have been by being unfaithful to its source material? I would suggest the 1968 version of Planet of the Apes, which was loosely based, of course, on Pierre Boulle’s 1963 novel Monkey Planet. I suspect any attempt to accurately reflect Boulle’s novel on film utilizing 1968 filmmaking tech would have been dead on the screen. Rod Serling made all the right choices in his script, which resulted in a film that has had a powerful impact on the public consciousness and left us with several unforgetable images (the end shot of the Statue of Liberty, in particular).

Jump into this, won’t you? Which films based on novels (or graphic novels) do you feel would have been improved by hewing more closely to their source material? Or which were damaged by the filmmakers’ attempts to be overly faithful to the written word? Comments are open!