This past weekend, I re-watched The Legend of Hell House, the 1973 horror film based on Richard Matheson’s novel, Hell House (Matheson wrote the script for the film). I hadn’t seen it in a number of years. Roddy McDowall is featured as Ben Fischer, a physical medium who, as a teenager, was the only survivor of a previous scientific expedition to the titular haunted house. He barely escaped with his life fifteen years earlier and is only convinced to join the present expedition by a promised $100,000 payment from a dying millionaire who wants to obtain proof of life after death. Ben is determined to keep his head low through the week he is instructed to spend inside the Belasco House, cutting himself off psychically from the house’s poltergeists; but he is forced into a more active role by the deaths of two of his compatriots and ultimately emerges triumphant over the malign spirit of Emeric Belasco, the perverted, evil former owner of the house.

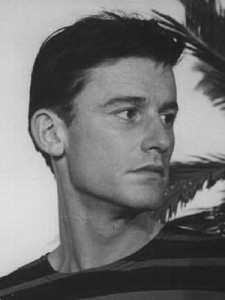

What really struck me about McDowall’s performance was the compelling power and finesse of his voice. McDowall was gifted with an extraordinary vocal instrument. During much of his career, he, along with Montgomery Clift, exemplified the vulnerable, sensitive, often wounded male – Clift with his face, and McDowall with his voice. In The Legend of Hell House, McDowall was called upon to present an extraordinary range of emotions, from meek, fearful passivity to scornful, mocking sarcasm; from desperate cowardice to determined self-sacrifice; and from near-helpless terror to a vengeful, furious, nearly megalomaniacal triumph. And at least seventy percent of his performance came through his voice. He would have been a superb radio drama actor during the Golden Age of Radio.

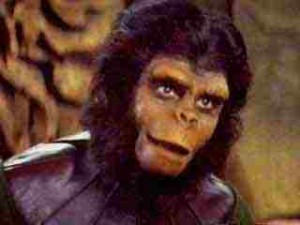

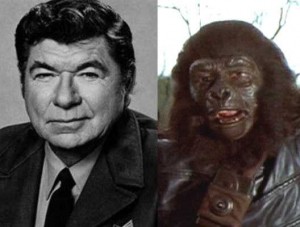

Roddy McDowall’s best-remembered roles were as Cornelius and Caesar in four of the original five Planet of the Apes films. He is as closely identified with POTA: The Original Series as William Shatner is with Star Trek: The Original Series (McDowall and Shatner made opposite migrations with their best-known properties: Shatner from the small screen to the big screen, and McDowall from the big screen to the small screen, but very briefly). McDowall would have appeared in all five films had not a job directing a film in Scotland kept him away from the production of Beneath the Planet of the Apes. Apart from the John Chambers simian makeup (ground-breaking for its day) and their convoluted, time-bending plots, the films are probably best remembered for the sound of Roddy McDowall’s voice: as Cornelius begging his wife Zira to be more sensible, and as Caesar pointing out the hypocrisies and injustices of human treatment of apes or leading battles against human oppressors.

Yet Roddy McDowall’s is far from the only memorable voice talent employed by the makers of the original Planet of the Apes films. The series is replete with them. The casting directors pursued the very wise strategy of selecting actors with strong, unique, memorable voices, realizing that the John Chambers makeup and the bulky costumes would cloak most of the actors’ subtle facial expressions and body language. Also, although Chambers made great efforts to physically differentiate his various chimpanzee, gorilla, and orangutan major characters, ensuring that each character had a very distinctive voice would help audiences keep the characters straight, so they would not confuse Cornelius with Milo or Dr. Zaius with Dr. Honorious. No casting director was listed in the credits for the original Planet of the Apes, but the Internet Movie Database credits Joe Scully with unit casting and Carl Joy with atmosphere casting (I presume the latter means casting the extras, of which there were many in each of the films). I suspect that producer Arthur P. Jacobs had a major hand in making casting decisions (his wife, Natalie Trundy, appears in four of the films, as the mutant Albina in Beneath, as Dr. Stevie Branton in Escape, and as chimpanzee Lisa in Conquest and Battle).

To whomever the credit goes, casting certainly proved to be a major strength of the original series. Many lines of dialogue from the films have entered the shared cultural lexicon (to be endlessly parodied on shows like The Simpsons). I’m sure you remember these:

“Get your stinking paws off me, you damned, dirty ape!”

“Beware the beast Man, for he is the Devil’s pawn…”

“You maniacs! You blew it up! Ah, damn you! God damn you all to hell!

“The only good human… is a dead human!”

“He bleeds! The Lawgiver bleeds!”

“I reveal my Inmost Self unto my God.”

“So, cast out your vengeance. Tonight, we have seen the birth of the Planet of the Apes!”

“Then God in his wrath sent the world a savior, miraculously born of two apes who descended on Earth from Earth’s own future. And man was afraid, for both parent apes possessed the power of speech.”

“Ape has killed ape! Ape has killed ape!”

If you’ve seen the films, and if those lines are at all familiar, I’m sure you remember them in the distinct voices of the actors who spoke them: Charlton Heston (as George Taylor), Roddy McDowall (as Cornelius and Caesar), James Gregory (as General Ursus), Don Pedro Colley (as the mutant Ongaro), and John Huston (as the Lawgiver). None of their voices could be confused with any other voices in the films. Each voice lingers in the memory like a familiar pop tune.

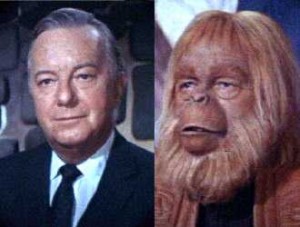

Originally, the part of Dr. Zaius in the first film was to have been filled by Edward G. Robinson, who actually did a screen test in an early version of the ape makeup. He ultimately backed out due to concerns about the amount of time he would need to spend in the make-up chair. His role was eventually filled by an actor with an equally distinctive voice, Maurice Evans. Still, it’s amusing to think of Dr. Zaius being voiced by the inimitable Edward G. Robinson, he of Little Caesar and Scarlett Street fame:

“I’m Little Zaius, see?”

“Mother of mercy… is this the end of Zaius?”

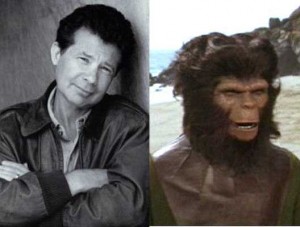

Lou Wagner is no household name, but he also has a voice more than capable of slicing through layers of heavy makeup. Fans of Star Trek: the Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine will immediately recognize his voice as belonging to DaiMon Solok and Krax, respectively. In the first Apes film, he played Lucius, a chimpanzee, Zira’s nerdy, socially conscious student nephew. His high-pitched, reedy voice fit the character perfectly and made him a suitable comedic foil for the dignified, austere Charlton Heston.

Claude Akins also has a voice with which most TV viewers of a certain age will be very familiar. He played Sheriff Lobo in the 1970s TV series B. J. and the Bear and trucker Sonny Pruitt in Movin’ On from the same decade. Prior to his TV work, he was a supporting actor in many prominent films of the latter portion of Hollywood’s Golden Age, including From Here to Eternity (1953), The Caine Mutiny (1954), and The Killers (1964). During the early days of television, he was a frequent guest star in popular westerns, including Wagon Train, Laramie, The Rifleman, and Gunsmoke. Horror fans will likely remember his wonderfully funny portrayal of Kolchak’s editor boss in The Night Stalker (1972). Akins played the gorilla Aldo in the final original Apes film, Battle for the Planet of the Apes (1973). Supposedly he was chosen for the role because, apart from the facial prostheses, he didn’t require the body portion of the ape costume – he already looked like an ape. I’m certain the real reason he was selected, though, was for his voice, perfect for Aldo, capable of expressing brutishness and a childlike naiveté simultaneously.

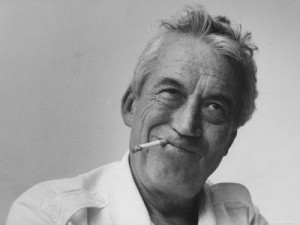

One of Akins’ costars in Battle was veteran director/actor John Huston, possessed of one of the most distinctive and memorable voices of the American stage or screen. Huston’s career is awe-inspiring in its scope, longevity, and enduring aesthetic quality. Not many other filmmakers can list on their resumes having directed such classics as The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, The African Queen, and Fat City, as well as turning in unforgettable performances in films such as Chinatown. He was perfectly cast as the wise, gentle, saintly Lawgiver, his gravelly voice lending its gravitas to ape scripture mumbo-jumbo that probably would’ve sounded silly coming out of most other actors’ mouths.

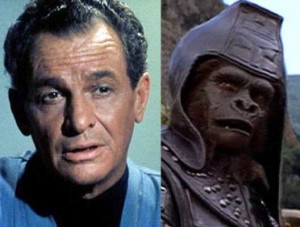

In casting about for other memorable American or British voices which could have been lent to an ape, I thought of Orson Welles. Turns out I wasn’t the first to do so. According to the documentary Behind the Planet of the Apes, Welles was offered the role of gorilla General Ursus in Beneath the Planet of the Apes, but he turned it down. Perhaps by that time in his career, he had grown (sideways) beyond the capability of mounting a horse. Or maybe, like Edward G. Robinson, he didn’t relish the thought of being cooped up in a make-up chair for three or four hours a day. However, the casting director didn’t miss a beat in finding a replacement. At this point in time, I cannot imagine anyone but James Gregory mouthing the line, “The only good human… is a dead human!” Gregory was capable of embodying arrogant swagger with his voice, and he certainly did so as General Ursus. Another wonderful aspect of his performance is that he was so obviously having a grand old time going ape; his enthusiasm is infectious. Genre fans will recognize Gregory from two episodes of the original The Twilight Zone, The Manchurian Candidate, and an episode of the original Star Trek, “Dagger of the Mind.” TV comedy fans will remember him from his many seasons as Inspector Luger on Barney Miller.

Another well-known TV comedy/science fiction actor, Jonathan Smith, best known as the sniveling, always scheming Dr. Smith of Lost in Space, was offered a role in the first Apes film; John Chambers had tested out an early version of his ape make-up in an episode of that series. But Smith, having seen up close what was involved in the application of the make-up, took a pass. A shame… with that superior sneer of his, he would have made a wonderful orangutan.

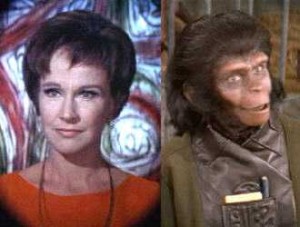

One prominent actress from the series, although possessed of a wonderful, highly emotive voice, was cast, I believe, for her unique ability to act right through her chimpanzee make-up, to project her facial expressions, particularly those of her eyes, right through all the layers of latex and spirit gum. This was Kim Hunter, who portrayed Zira in the first three films. Here’s a prescription for a fun evening: rent/download A Streetcar Named Desire and Escape From the Planet of the Apes and watch them back to back. I guarantee that, while watching the latter, you’ll exclaim while watching Zira, “Good lord, it’s Stella Kowalski!” and while watching Stella in the former movie, you’ll blurt out, “My God, it’s Zira!” Kim Hunter’s electric persona leaps off the screen in both films, make-up be damned (in Escape). I’ve got a feeling they could have dressed her up as the Elephant (Wo)Man and viewers would still think to themselves, “Good lord, it’s Stella Kowalski!” That’s how strong her screen personality was.

I honestly don’t remember much about the vocal talents on display in the Tim Burton remake (although I suppose I would have to give Helena Bonham Carter kudos in that regard). For me, all the energy that film might have possessed was swallowed up by the black hole of Mark Wahlberg’s sleepwalking performance as the film’s astronaut protagonist. I don’t know whether he made a conscious decision to portray the anti-Charlton Heston, dialing his own charisma down to zero, or whether he just decided to collect his paycheck, but he sank that film as surely as a Japanese Long Lance torpedo sank the USS Indianapolis.

I haven’t yet seen the 2011 reboot of the series, Rise of the Planet of the Apes (apparently a very loose remake of Conquest of the Planet of the Apes). It marks a departure from tradition in that all of the apes are computer generated. It received much better reviews than its Burton-helmed predecessor, and its producers would like it to be the start of a new series of Apes films. If I may give them one bit of unsolicited advice? Listen to the original five films with the picture turned off, concentrating on just the voices; and choose your ape vocal actors with care. For the voices will make or break your films, lingering in audiences’ minds long after the visual novelty of the CGI gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans has faded.