The House on the Borderland

William Hope Hodgson

Original edition: Chapman and Hall, 1908

Most recent edition: Echo Library, 2006

Most classic books are gazelles. They are pleasantly proportioned, graceful in their operation, and do a number of things very well. They provide rich portraitures of characters a reader comes to care for and identify with; they immerse those characters in a detailed, memorable setting; they lay out a series of events which are of intense interest to the characters (and thus to the reader) and which, in retrospect, create a meaningful and aesthetically pleasing pattern; and they do all of this with a style of language which is itself aesthetically satisfying.

Other classic books, however, far fewer in number than the gazelles, are fiddler crabs. As aesthetic creations, they have no symmetry whatsoever and are not pleasantly proportioned at all. Many of their elements are stunted or misshapen. But they possess one quality, perhaps two, of the highest merit; elements which are so unique or memorable that they singlehandedly lift the book they are contained within out of the great mass of the unremarkable and mundane. Acting like a fiddler crab’s single massive claw, they beat down the door of Immortality and drag their book across the threshold, into the rarified realm of Books Which Shall Be Remembered.

William Hope Hodgson’s third novel, The House on the Borderland, one of the recognized classics of weird fiction and cosmic horror, a precursor to the works of H. P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, Mervyn Peake, and China Mieville, is a fiddler crab.

A novel can be thought of as a chair with four legs: characterization; plot; setting/mood; and language. “Theme” can be considered the seat of the chair, a quality supported by and arising from the four legs. The House on the Borderland is greatly lacking in characterization or development of character; it follows no aesthetically pleasing pattern of plot; and its language is, at best, pedestrian or serviceable. What make it a classic of its genre, a Book Which Shall Be Remembered, are Hodgson’s remarkable, captivating construction of the book’s settings and his steady building of a mood of mounting dread, vulnerability, and helplessness before unknown cosmic forces.

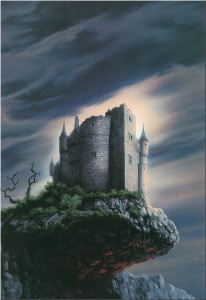

Let’s examine what might be considered the book’s shortcomings first. We readers gain very little insight into any of the characters in the novel. The framing plot, that of two men on a fishing holiday in rural Ireland in the late nineteenth century who come across the ruins of a house precariously located on an outcropping of rock above a desolate and oppressive crevice, and who discover in those ruins the partially legible diary of the home’s former owner, is rudimentary. We learn nothing of importance about these two men; they are present in the book merely to deliver to us, the readers, the contents of the diary. The never named author of the diary is the book’s protagonist. Despite the fact that the majority of the book is told in his own words, from his viewpoint, we learn very little about him, either. All that we are told is that he is elderly but still physically vigorous, that he has moved to an isolated house in the Irish countryside with only his sister and his dog as companions, and that he once had a great love, whom he lost. We never learn his reasons for moving to the isolated house. The only reason we are offered for him staying there after repeated attacks upon him, his dog, and his home by what he calls the Swine Things is that being in the house somehow provides him with a tenuous spiritual connection to the soul or spiritual embodiment of his lost love. He is shown to have an out-of-body experience that takes him from nineteenth century Ireland to the very center of the universe, uncountable eons in the future; yet this astounding, inexplicable journey through space and time does not leave any appreciable impact upon his character or outlook. He is no different at the end of his journal entries than he was at the diary’s beginning. The most well-rounded character in the book, I believe, is his dog, Pepper.

The plot? It most definitely develops forward momentum during the book’s first half, when the protagonist is exploring his mysterious house and the rapidly changing landscape which surrounds it, and when he is engaged in fending off the attacks on his hastily fortified home from swarms of Swine Things, which emerge from a growing canyon and from caverns which extend beneath his house. In this portion, the book is suspenseful and gripping. Yet when the attacks die down (for no reason of which we readers are made aware), the book shifts into a cosmic travelogue/fantasia when the protagonist begins experiencing time in an ever-accelerating fashion. In an unexplained transformation, he leaves his dust-heap of a body to witness the aging and ultimate death of the Sun, the destruction of the Earth and all the planets of our solar system, the capture of the dead Sun by the gravities of other celestial bodies, and its final arrival at the center of the universe, where its plunge into the surface of the Central Sun sends the protagonist catapulting across multiple dimensions to land on the alien plain from which the Swine Things may have come. During the latter part of these fantastic, unexplained travels, the protagonist experiences periods of reunion with the spirit or essence of his lost love. Yet throughout this portion of the book, the protagonist is presented to us readers as a detached observer, untouched by any of the cataclysmic events we are so powerfully shown. With about a fifth of the book remaining, the protagonist is shown to return to his house, apparently several days after his epic journey through time and space began. It seems to have had no more effect on him than a particularly vivid dream. The book then returns to its earlier mode of accumulating horror, and the last we see of the protagonist, he is falling victim to an attack far more insidious and less escapable than the prior attack by the Swine Things. The novel’s framing story ends abruptly when the two tourists decide, rather wisely, to get the hell out of Dodge and leave rural Ireland and its crumbling house of mysteries behind.

One experiences this book much like one would an extended dream (or drug hallucination, perhaps). Therein lies much of its power and enduring appeal. The novel enfolds a reader like a scented cloak, blocking out all outside light and stimuli during the experience of reading it. Incredible events occur without reason or explanation. The protagonist, although portrayed as a resourceful, clever, and capable man, is mostly helpless in the grip of malign, alien forces, a tiny speck of a rag doll tossed about by dark, unknowable gods and a tsunami of cosmic evolution. One cannot escape the sense that matters can always get worse, and they most probably will. If the book delivers a message or contains a theme, it is this: we are alone. There is no benevolent God to aid us, upon whom we can call. We are helpless and of no significance. There are Things Out There that can squish us at will, and we will never know when it will happen, nor why.

Entirely on the basis of its settings and its mood, this novel can be considered the fountainhead of two subsequent streams of fantastic literature. I believe virtually the entire corpus of “Isolated Individual versus Hordes of Homicidal Creatures” stories, from Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (and its film versions) to the latest episode of The Walking Dead, can be traced back to the nocturnal invasions of the Swine Things. Perhaps of greater significance, Hodgson extended his imaginings of the future of our planet, the solar system, and the entire universe far beyond what even H. G. Wells had attempted to show in The Time Machine or any of his prophetic novels. Hodgson may be said to have imaginatively blazed the trail for such science fiction greats as Olaf Stapleton (whose Last and First Men and Star Maker show significant similarities to the cosmic travels portion of The House on the Borderland), Jack Williamson, Edmund Hamilton, and Arthur C. Clarke.

By the way, William Hope Hodgson lived an extraordinary life, apart from his four novels and many dozens of short stories and poems. Born in 1877, the son of an itinerant Anglican priest (one of whose parishes was in County Wicklow, Ireland, where The House on the Borderland is set), Hodgson ran away as a teen to become a merchant seaman. According to one of his biographers, Sam Moskowitz, Hodgson developed a great fear of and loathing for the sea, which is somewhat surprising, given his lengthy career in the merchant marine. A small man with delicate features, he was subjected to withering physical abuse from his fellow seamen, so much so that he developed a personal program to build up his body and his fighting skills, enabling him to defend himself. After he left the merchant marine, he became a turn-of-the-century version of Jack LaLanne, setting up a school of physical culture and body-building. He trained English police forces and even was involved with Harry Houdini for a time. When that business venture failed, he turned to fiction writing, and he and his wife moved to France for a number of years. They returned to England at the beginning of World War One, when Hodgson made his first of several successive enlistments in the British Army. He was killed in Ypres, Belgium in April, 1918, at the age of 40, just seven months prior to the armistice and ten years after the publication of The House on the Borderland.

I have just re read The House .. after first encountering it in 1975. It and The Night Land have been part of my small fantasy library since I was teenager.

I had cause to recommend The House .. to my teenage daughter looking for an example of Gothic writing for a year 12 english essay.

You’ve written a wonderful review .. that will greatly help frame a youngsters (and her old dad’s) appreciation and analysis of the text … and will be cited accordingly.

many thanks !

gtb

Dear Guy,

Your note made my day. I’m so pleased I was able to help out your daughter! Good for you, to direct her to such a wonderful vintage book.

This was a good review, and I’m glad that I found while searching material about Hodgson’s books. I’ve read both Night Land (or rather, Stoddard’s modernization because the faux Elizabethan style forced me to quit the original halfway through) and The House etc, and was wondering what’s the magic with Hodgson is. I mean that while reading the books, I was often annoyed by the rather soulless characters and tottering plotting. On the other hand, I had such strong images of the settings, especially the Night Land, in my mind that I couldn’t stop reading. The conceptions are so strong and compelling somehow that despite the flaws the books were quite gripping. Maybe it’s precisely the feeling of an invididual against inscrutable forces infinitely stronger than he, that you also alluded to.

As for the House on the Borderland specifically, I disagree on one point with you. You make it sound like the novel says there’s no God. For me, on the other hand, the Central Suns in the Recluse’s vision are a clear metaphor of the Divine. Everything seems to return to them, and to emanate from them. The glowing spheres with their either serene or suffering inhabitants are a stand-ins for Heaven and Hell, respectively. The red plain is certainly Hell, as the most evil pagan gods are there.

Certainly, this is a far cry from the biblical idea, if strictly viewed. Maybe Hodgson is trying to convey an idea of some sort of panteistic, dispassionate deity with both evil and good side (hence the double Central Suns, the other glowing, the other dark). But still, there certainly are good and evil as the fates of the souls on the orbs show. Or then again, maybe that is a metaphor for how a human can construct a private heaven or hell for himself.

The book is truly both a maddening and compelling one. It is so near to being a masterpiece. Livelier language, cutting the vision in the middle by maybe one half and making the scuffle with the monsters a bit longer could make wonders in my opinion and really let the ideas shine. Let’s hope someone makes a relatively faithful remake of this, like Stoddard made of the Night Land.

[…] Andrew Fox supplies the parallax on this one by looking, among other things, at how this stands at the beginning of the tradition of horror stories with an “Isolated Individual versus Hordes of Homicidal Creatures” […]