I made the big jump that September. By October, 1990, I was comfortably (if tightly) ensconced in a “slave quarters” apartment located in the backyard of a clapboard house in Mid-City, New Orleans, just blocks off famous Canal Street. I found myself a part-time job as a program assistant with Tulane University’s Hillel Foundation, where I’d gone for Friday night services and dinners as a student. And since I didn’t have to show up for work until the afternoon, I was free to spend every night, up until the wee, wee hours, with my new Panasonic laptop at Borsodi’s.

Borsodi’s Coffeehouse (later called Breezy’s Place, after Bob moved his business from Freret Street to Soniat Street) enjoyed three incarnations in New Orleans, following the blooming and dying off of at least ten other sequential locations on the East and West Coasts, including New Haven and Santa Barbara. In 1990, it was located on Freret Street, a down-at-the-mouth business district a half-mile east of Tulane and Loyola Universities. The strip had been going downhill ever since the city’s only kosher butcher was murdered in front of his shop in 1980. The city had tried to revitalize the corridor by repairing the street (a godsend in New Orleans, which is cursed with the worst road conditions of any city in America) and enforcing code restrictions, but it hadn’t resulted in much improvement.

Borsodi’s shared the block with a college bar, a dingy washateria run by a woman owner with the customer relations skills of a warthog (yes, as a Loyola student I used to do my laundry there), and an abandoned building, missing part of its roof, which served as headquarters for the local pharmaceutical sales reps. Borsodi’s didn’t look like much from the outside. It didn’t even have a sign. When the city decided to enforce code, it forced Bob Borsodi to take down his hand-painted sign. He refused, on principle, to replace it with a professionally manufactured one.

But inside. . . ah, inside was a whole different story. Borsodi’s was like no other place in New Orleans; maybe no other place in the country. Try to imagine a three-dimensional collage the size of a carpet warehouse, and you’ll have some idea of what it was like. Every square inch of walls, ceiling, and floor (and much of the furniture) was covered with a menage of music posters, poetry reading leaflets, covers torn from old comic books, newspaper headlines, cartoons, cheap prints of Renaissance masterpieces, assorted graffiti, and original paintings and artwork. You could spend a week in there just reading the walls, never even getting to the hundreds of poetry books and old National Geographic magazines scattered around.

Despite all the distractions (among them plentiful acquaintances who all wanted to talk, plus pretty decent live klezmer music on Friday and Saturday nights), I was able to get a lot of work done at Borsodi’s. The traditional rule of thumb for writers is that you need to write half a million words of shit and get them out of your system before you can write anything good. I wrote a fair portion of my half-million shit words at Borsodi’s, most of them part of a very lengthy, self-consciously literary novel set in Miami during the year of the Mariel boatlift and the Liberty City riots. And yes, I was alone, briefly, gloriously unique, as the very first writer, aspiring or otherwise, to ply his trade on a laptop computer at Borsodi’s Coffeehouse, busily flipping between my WordPerfect program diskettes on that single 3.5″ floppy drive.

My finest Borsodi’s moment, laptop-wise, came early in 1991, during a Tuesday night poetry reading. Bob typically sponsored a monthly poetry reading on the first Tuesday of each month (excluding summer months, when the place was closed down so he could jump a freight train and head somewhere less humid than New Orleans). One month the poetry reading snuck up on me. I was sitting in my corner, typing away on my Panasonic, when Bob invited me to read some of my poem on stage. I could never say no to Bob; the only problem was, I’d left my binder of poems at home. However, I did have copies of all of my poems with me, etched in silicon on a floppy in my laptop case.

So I took the Panasonic up on stage and set it down on the lectern, likely rescued from one of Tulane’s garbage bins. I read four of my poems off my laptop’s screen, pausing a bit in awkward places while I hurriedly scrolled from one screen to the next (the keystrokes, for those of you who never used the old DOS WordPerfect, are Home-PageDown). It was, if you’ll excuse a little bragging, an historic moment–the first time (and maybe only time) a poet (or poetaster) performed with a laptop on stage at Borsodi’s Coffeehouse. Bob, in his taciturn, wry way, was very impressed. I’m sure the other Bob, my ex-boss from Long Island, would’ve been proud of me, too, although he didn’t care much for poetry. The other readers thought it was pretty cool. It came close to being performance art.

Not long after, however, my little Panasonic came to an inglorious end. In August, 1992, the Gulf coast was thrown into a tizzy by the march across the Atlantic of a hurricane with my name on it. Hurricane Andrew. After tearing up my birthplace (Miami, Florida) and not finding me there, Andrew headed straight across the Gulf of Mexico for New Orleans. At the very last minute, Amanda (my then fiancée, later my wife, later still my ex-wife) and I decided to head for higher ground; i.e.: Arkansas. Loading my desktop Tandy into our car was out of the question; the best I could do was move it away from the windows and cover it in a plastic garbage bag. But the Panasonic and all my floppies were coming with me, through hell or (gulp!) high water.

We headed down the stairs of our apartment building, our arms loaded up with our valuables, our heads swimming with terrible visions of bumper-to-bumper traffic on the I-10. The Panasonic was in its (so pathetically flimsy, I could kick myself) carrying case, its strap slung across my over-burdened shoulder. We got down to my car, a little red Ford Escort station wagon. Struggling, over-hasty, I dug the keys out of my pocket and unlocked the rear hatch. In the middle of this convoluted maneuver, the Panasonic slipped off my shoulder.

Laptops do many things very well. One thing they don’t do well is bounce. My little computer hit the curb after a four-foot drop. Hard.

The wind stopped its howling. The racing clouds high above stopped their racing. The whole storm-tossed world stopped dead, held its breath, and winced while I screamed, “NNNOOOOOOOOO!!!!”

Sick to my stomach, furious with myself, and filled with dread, I opened the case. There was no visible damage. Operative word: visible.

I finished loading up the car. We fled west, then north. Our evacuation was surprisingly traffic-tangle-free; most folks who decided to get out had done so earlier than we did, then snatched up all the motel rooms for three hundred miles around. I got to visit the ironclad gunboat U.S.S. Cairo at the Vicksburg National Battlefield, something I’d always wanted to do. We ended up at my future mother-in-law’s home in Texas. Andrew made landfall eighty miles west of New Orleans, devastating Morgan City and delivering only the slightest of glancing blows to the Big Easy. But after that harried, rain-tossed morning of headlong flight, the battery of my beloved little Panasonic would never charge again.

I was still able to use it for a while after that. I just always had to plug it into a wall socket, which kind of defeated the whole purpose of a laptop. Yet the indignities didn’t stop with that; the fall was the start of a swift, precipitous decline for my first little machine. From then on, my Panasonic was like a thin-boned elderly person who breaks a hip falling in the bathtub–the initial injury leads to gradual immobilization, loss of will to live, confinement to a hospice, and finally, the grave. I knew the end had arrived when its sole floppy drive stopped working.

Not ready error reading drive A

Abort, Retry, Fail?

On a machine running off a single floppy drive, this was a death sentence. Fail, Fail, Fail. No WordPerfect. No creating new files. No accessing old files. Nada. My $1100 laptop computer had just become an $1100 paperweight.

I quickly came to the sad realization that my machine wasn’t worth repairing. Although only three-and-a-half years old, the Panasonic’s retained value was well below what it might cost me to get it fixed. Rather than venture out into the dismal swamps of the laptop repair market, I decided to shell out around $300 and buy a used, refurbished laptop through the mail. Not only would I get a working machine, but I would also significantly upgrade, moving beyond the Panasonic’s 8086-class chip and vulnerable single floppy drive to a 286-class (or maybe even 386-class) laptop with a hard drive.

The broken Panasonic sat in my closet for years, gathering dust and cat hair, until the summer of 1997, when a teacher friend of mine was looking for donations for her school’s garage sale fundraiser. The whole caboodle, including laptop, case, extra battery, manuals, and MS-DOS 3.3 on floppy diskette, ultimately sold for the princely sum of fifteen dollars, or less than two percent of its original purchase price.

It turned out to be only the first of many, many laptops I would end up giving away.

* * * *

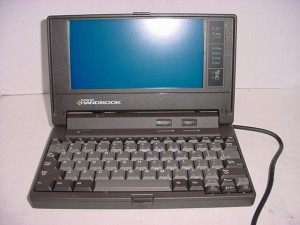

My second laptop was a real honey. A Gateway 2000 HandBook, the original model with the NEC V30 microprocessor, roughly a 20286-equivalent chip. I bought it used in 1994 for what seemed to be a steal: $300 from a computer liquidation mail order company, less than a third of its cost when new. I’d wanted one ever since it had come out. Really wanted one. I’d never forgotten Gateway 2000’s print ads for the HandBook–the first sub-three-pound IBM-compatible to both have an internal hard drive and run on standard alkaline batteries. The guy shilling the computer was a dog sled racer. According to the ad, he’d take the HandBook with him on his Iditarod Trail races to help keep track of the daily performance and health status of his sixteen sled dogs.

Never, not even in my wildest imaginings, did I have any expectation that I’d ever race dog sleds across frozen tundra in Alaska (or anywhere else). But the notion that the HandBook could survive sub-zero temperatures, be light enough to fit on a dog sled, and run indefinitely on common-as-dirt AA batteries was magnetic. I fell victim to the same forces of aspirational marketing as those which capture millions of buyers of sport utility vehicles each year–who never drive their knobby-tired jungle excursion trucks on anything so rough as even a dirt road. Almost exactly three years after I first read that ad, I had my HandBook in hand, ready to take on the world (or a pack of sled dogs).

Did I ever use the HandBook in the snow? Certainly not; I am many things, but a masochist is not one of them. I never even ran it off the optional AA alkaline battery pack (my used machine didn’t come with that desirable accessory, and although the infinite rummage sales of eBay later brought me several additional HandBooks, some which came with the hollow, plastic alkaline battery holder, I was never able to get one to power up any of my various little Gateways; I haven’t futzed with one in a few years, so maybe it’s time to try it again).

But, unlike the six-pound Panasonic, the three-pound HandBook went with me everywhere. There is a tremendous difference between six pounds and three pounds; try toting the former in your right hand and the latter in your left for a half hour and compare the aches in each shoulder and wrist. I brought the HandBook with me daily to the office (at the beginning of 1993, I’d started managing the Commodity Supplemental Food Program for the Louisiana Office of Public Health’s Nutrition Section), just in case I came up with a story idea or some new notion for my latest big project, a horror novel set during the Civil War called Fire on Iron.

I took it to my local PJ’s Coffeehouse, where Wife #1 worked a few shifts to supplement our income while she was going to nursing school, and busily typed away on its small but serviceable keyboard, spinning the battles and mishaps of ironclad gunboats on the Mississippi and Yazoo Rivers. I took it with me on trips to New York City and Albuquerque. I loaded it into my backpack and bicycled from my apartment near City Park to the edge of Lake Pontchartrain and sat on a bench by the seawall and typed.

I even bought a teeny-tiny pocket modem for it, about the size of a D battery, a sizzling 1200 baud unit, so I could sign up for CompuServe (the original DOS text-only version, which would run on machines with sub-386 processors and only 640K of memory). Unlike the later World Wide Web, CompuServe’s network proved to be of limited interest to me; I toyed with some of the forums devoted to science fiction or to the HandBook and palmtop computers (this was how I first learned of the Poqet PC), but ultimately the task of setting up the modem, etc., seemed to not be worth the moderate effort. Wife #1 continued to use CompuServe to email old high school friends.

The HandBook provided its most yeomanlike service during the first three hectic years of my running the New Year Coalition, the New Orleans-based campaign against holiday gunfire. On New Year’s Eve, 1994, my cousin Amy Silberman, a young magazine assistant editor visiting from Boston, was killed by a falling bullet while waiting for the midnight fireworks display next to the Riverwalk and Jax Brewery, at the edge of the French Quarter. Police estimated that more than two-hundred thousand rounds of ammunition were fired into the air that night by people using guns as noisemakers. Amy was one of about a half-dozen persons to be struck that evening, but she was the only one who suffered a fatal injury. For the next decade, I helped to run and served as the spokesperson for a public awareness campaign to educate gun owners and their families about the simple facts of ballistics. What goes way, way up comes down fast and hard, hard enough to penetrate the roof of a car, an apartment window, or a skull.

The HandBook served as an invaluable two-pound assistant. I’m not an especially organized person, and I suddenly found myself dealing with hundreds of volunteers, neighborhood associations, police officials, politicians, businesspeople who wanted to donate goods and services, and reporters from newspapers and TV stations. Left to my own devices, I would end up with a wallet and pockets bulging with smeared, crumpled business cards and sticky notes.

Knowing this was a recipe for failure, I invested in a tidy little program called MemoryMate, a memory-resident, free-form database into which I could type contact information, appointments, notes for speeches, reminders, and drafts of New Year Coalition letters, all without having to format anything or select from various different programs. It was kind of a magical filing drawer into which I could throw all my papers and business cards and sticky notes and have them wondrously sorted into logical folders the next time I opened the drawer. It reminded me when I was about to forget something and helped prevent me from procrastinating.

It pretty much saved my ass–even with the help of the HandBook and MemoryMate, I still teetered perilously close to the edge of a nervous breakdown during the latter portions of 1995 and 1996. I couldn’t escape the haunting, corrosive notion that if I didn’t do my job right, if I didn’t give 110% effort at all times, throw my whole heart into every speech, meet with every Neighborhood Watch organization in the city, make sure that every last poster and leaflet got taped up in some public place, another man or woman would die on New Year’s Eve like Amy had. And, somehow, it would be my fault. Because I hadn’t done enough.

But the campaign–thank God and thank the people of New Orleans–did what it was meant to do. It convinced the mass of non-malicious shooters, people of good will who had been ignorant of the potentially deadly consequences of their celebratory habit, to get off the streets with their guns. This made it possible for the police to hone in on the hard core of gangbangers and criminals who took advantage of the temporary anarchy every New Year’s Eve. Prior to the campaign’s success, the cops had parked their cruisers beneath overpasses during the hour surrounding midnight, as vulnerable to the hail of falling bullets as anyone else. The volume of gunfire plunged, and arrests and weapons confiscations went up at the same time. Since Amy’s death, no one else has been killed in New Orleans by holiday gunfire.

Unfortunately, my marriage, not built on the firmest of foundations to begin with, suffered stress fractures. Coincidentally, so did the plastic hinges on the HandBook’s screen. A common problem with this model, as I was to learn. The plastic housing surrounding the LCD screen began splitting at the seams a little worse each time I closed the lid. I tried Super Gluing it, but my fix didn’t hold. I tried again, but my second attempt just made the problem worse.

Oy, what a metaphor for my marriage situation in early 1997!–Amanda was rapidly drifting away, and the harder I tried to pull us together, the more desperately I flailed, the more distant and disdainful she became. After graduating nursing school, which I had paid for, she went off on a six-week Servas road trip (which I also paid for) through California and the Northwest. . . by herself. Much of nursing school and the road trip were “paid for” with my credit cards. I figured, hey, we’ll be DINKs soon–dual incomes, no kids–so we’ll pay off all the debt within a year or so, no sweat. Seemed like a sensible plan at the time; what could go awry?

She threw me a bone by suggesting we do more active, athletic activities together. Like a grateful, slobbering Golden Retriever, I jumped happily all over this idea. She liked rollerblading. I suggested that I also rent a pair and that we go rollerblading together in Audubon Park on Good Friday, when I had the day off from work. I had never been rollerblading before, but I’d skated on conventional roller skates as a kid. How different could it be?

I got wrong-footed almost immediately. After renting the rollerblades, I had a difficult time putting them on, but Amanda had no patience for my thick-fingered fumblings. Rather than making sure I’d laced the boots up tightly enough, she headed out onto the bike and skate path that encircled the park, telling me she’d loop back around and catch me when I was done.

I did the best I could with the boots, then gingerly stood and began slowly propelling myself forward. I surprised myself by becoming semi-competent fairly quickly–not as good as the average eight year-old, perhaps, but good enough to make it around the 1.5 mile loop without falling. Amanda passed me. I smiled and waved–Look at me, honey! I’m doing GREAT! Then hubris took over, which quickly turned to nemesis. Rather than declaring victory and calling it a day, I decided to be a big macher and go for a second loop.

Half way around the track, I got tired, really tired. I felt myself losing my balance. I thought, You know you’re going to fall sometime, you’re wearing pads and a helmet–just let yourself fall and get this first tumble over with. I hit a rough patch of asphalt and pitched forward. As I saw the ground rapidly approaching my outstretched, padded palms, I felt my legs tangle together as the heavy boots, airborne now with my feet still in them, headed off on conflicting trajectories. When I landed, my right boot came down sharply on the ankle part of my left boot, with much of my weight on top of it, the force of impact multiplied by a velocity of at least ten miles per hour.

I howled like a banshee; I wailed like an air raid siren; I screamed like a little girl. . . insert your favorite cliché here.

A nice man with a golf cart drove me back to my car. The rented rollerblades didn’t get returned for a few days. The emergency room doctor at Methodist Hospital asked me when I wanted to schedule my operation. “What operation?” I asked, still believing I had suffered only a bad sprain. He showed me the x-ray. My left ankle had snapped in two places. A piece of my bone floated off by itself, like Australia in the South Pacific.

He placed my ankle in a temporary cast, handed me a pair of crutches, and referred me to an orthopedic surgeon. We scheduled the operation for the following Tuesday.

Boy, had my plans come a’ cropper! I’d wanted to do something athletic together with my wife, because that’s what she’d said she wanted, and what I’d wanted more than anything was to plug the holes in our relationship. But here I was, stuck on crutches for the next two to three months, essentially a temporary cripple, a burden on Amanda, rather than the fun companion I’d tried to be. The night after the accident, a half hour before Amanda needed to leave for her nursing shift, I told her all this. I told her how horribly helpless I felt to do anything constructive to repair our marriage, and I started crying.

She told me she couldn’t take this anymore. She said she wanted a divorce. And then she left for work. And I then got to experience one of the most wretched nights of my life. I found out four weeks later that she’d been seeing another man. And that was that. I said the hell with marriage counseling, which hadn’t been doing as any good anyway. I knew it was over. I told her I’d agree to the divorce.

Believe me, you don’t know what resentment is until your wife of four years, whom you’ve sent through nursing school, tells you she wants a divorce not long before you go under the knife. And then her new boyfriend calls her at your apartment while you’re lying on the couch with your leg in a plaster cast.

I was broken. My marriage was broken. And my laptop was broken, too.

Next: I get divorced. I get depressed. I get on an antidepressant. I buy a Poqet PC. I start dating again. I begin writing Fat White Vampire Blues. My Poqet PC helps me score with a French Canadian doctoral student. I rewrite her dissertation in linguistics. She dumps me. I buy my first house. I get what seems like a great idea…

The last third of this piece is heart-rending! You’ve woven so much into this story.