Return to Introduction

Return to The Space Merchants

Return to Search the Sky

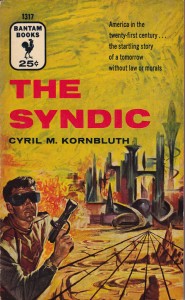

The Syndic

by C. M. Kornbluth

Original publication: Doubleday, 1953

Most recent publication: Armchair Fiction, 2011 (paperback double novel, included with Poul Anderson’s Flight to Forever); Wonder eBooks, 2009 (Kindle edition)

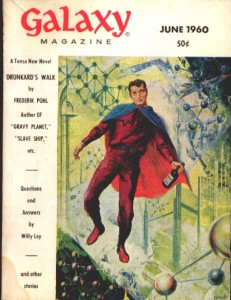

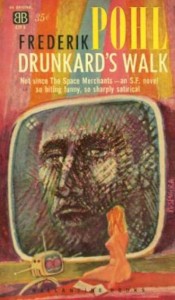

Drunkard’s Walk

by Frederik Pohl

Original publication: serial publication in Galaxy Science Fiction, 1960; Ballantine, 1960 (paperback original); Gnome Press, 1960 (hardback)

Most recent publication: Granada, 1982 (British pb)

Although their most famous and enduring work of the 1950s remains the novels that they wrote together, both Cyril Kornbluth and Frederik Pohl published numerous other books during that decade, both solo works and novels which they wrote with other collaborators (Kornbluth with Judith Merrill, and Pohl with Jack Williamson and Lester Del Rey). Kornbluth’s best-remembered solo novel of the decade is The Syndic, and Pohl’s best received solo novel of that period is Drunkard’s Walk (his only other solo novel of the decade was Slave Ship from 1956; solo novels from Pohl would remain relatively rare until the latter half of the 1970s, when his career experienced a second blooming).

By taking a look at these two solo novels, each written either during or shortly after the period of their most intense and sustained collaboration, we may be able to acquire a better sense of what qualities each partner brought to the collaboration. We may also get a clearer idea of both men’s weaknesses as novelists during this time in their careers, which will help us to better understand how their strengths were complementary, and how this complementariness contributed to the classic status of three of their four shared novels.

Fred Pohl had this to say about Cyril Kornbluth’s assets and weaknesses as a writer:

“Cyril had a nearly in-born gift for graceful writing and excellent spot-on characterization. His only real weakness was in plotting. By then he had taught himself — maybe with a little help from those Futurian writing orgies — plot structure for short stories and, soon thereafter, novelettes and novellas. Some of his work from that period I would match against almost anybody’s best stories ever, including ‘The Marching Morons,’ ‘Two Dooms’ and a good many others.”

It is very likely that Fred Pohl knew Cyril Kornbluth as well as anyone. How do Pohl’s observations above match up with what can be observed in Kornbluth’s best-known solo novel, The Syndic?

Pretty well, I think.

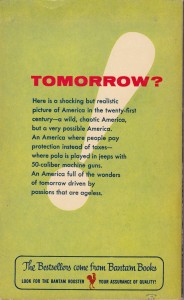

The Syndic’s central idea, that of a future American society based on anarcho-capitalism, in which organized crime has booted out the federal government, legalized itself, and runs things in a surprisingly humane fashion, is a sturdy one for a science fiction politico-satire. The Syndic is variously described by its members as “an organization of high morale and easygoing, hedonistic personality” and “an appropriately structured organization of high morale and wide public acceptance,” never as a government. The book may be viewed as one of the stronger extrapolations of libertarian social and political ideas in science fiction, and it has been awarded a Hall of Fame Prometheus Award by the Libertarian Futurist Society in 1986.

The novel’s central characters are fairly well sketched out and appealing. Charles Orsino, the hero, is a low-level bag man for the Syndic, a young man painfully aware of his low rank in the organization but who is loyal to a fault. His uncle, Frank Taylor, a financial administrator for the Syndic and a social theorist, the author of Organization, Symbolism, and Morale, is a humorously crusty old curmudgeon who obviously has a big soft spot in his heart for his nephew. Lee Falcone is a stand-out in that she is portrayed as both a highly competent woman professional (a psychologist) with an important role in the Syndic and as an attractive and desirable potential love interest for Charles (not a crone or a spinster or a battle-ax), a combination rather rare in science fiction during the period in which the book was written. A secondary character, Martha, a young, telepathic “witch” of a primitive Irish tribe, is especially appealing, a fascinating mix of naiveté, youthful over-confidence, willfulness, heroism, and sweetness. The novel’s primary villain, Commander Grimmel of the exiled North American Government’s Office of Naval Intelligence, is a less well-rounded character, but, even so, may be viewed as more carefully and intelligently drawn than most of the heavies which tormented the heroes of 1950s science fiction novels.

Several of the novel’s set pieces are especially well-written and gripping. The scene in which Charles and a junior officer of the North American Navy are surrounded in the Irish wilderness by a hostile tribe of pagan savages and must defend themselves with a dismounted fifty caliber machine gun is loaded with telling details, suspense, tension, and atmosphere. Cyril Kornbluth makes excellent fictional use of his personal experiences lugging a machine gun around the Ardennes Forest during the Battle of the Bulge. Also very good is the description of Charles’ amnesiac sojourn in the lower depths of New York’s waterfront while he is under the induced delusion that he is Max Wyman, a man who hates the Syndic and wants more than anything to become an agent for the North American Government; Wyman is an invented personality temporarily grafted to Charles by Lee Falcone in order to allow Charles to infiltrate the North American Government and learn whether that entity is behind the assassinations and attempted assassinations of Syndic family members (including an attempted hit on Charles himself). The waterfront scenes are very atmospheric, reminiscent of the work of the best noir writers of Kornbluth’s day.

Kornbluth also showed a deft touch with humor. Charles’s interactions with a woman shopkeeper from whom he collects what we would think of as protection money is both funny and nicely revealing of the relationship between the Syndic and much of the American population east of the Mississippi. When Charles is undercover in the North American Government’s stronghold in Ireland, I smiled at his reactions to the relatively puritanical sexual mores he discovers there, in contrast to the easygoing and open physical relations between the sexes he has become used to back home. One of the best humorous exchanges occurs during a high ranking Syndic family strategy meeting, where Uncle Frank describes the current state of much of Europe, which had no organization capable of picking up the pieces after traditional governments atrophied and died of their own bureaucratic sclerosis:

“‘The forests came back to England. When finance there lost its morale and couldn’t hack its way out of the paradoxes, that was the end. When that happens you’ve got to have a large, virile criminal class ready to take over and do the work of distribution and production. Maybe some of you know how the English were. The poor buggers had civilized all the illegality out of the stock. They couldn’t do anything that wasn’t respectable. From sketchy reports, I gather that England is now forest and a few hundred starving people. One fellow says the men still wear derbies and stagger to their offices in the City.

‘France is peasants, drunk three-quarters of the time.

‘Russia is peasants, drunk all the time.

‘Germany–well, there the criminal class was too big and too virile. The place is a cemetery.'”

The novel’s primary shortcomings seem to me to be in the area of plotting. Kornbluth ends The Syndic on a weak note, a philosophical dissertation by Uncle Frank on the proper limits of anarcho-capitalism which, although interesting and sure to provoke discussion among sociologists and political scientists, brings the book to a close on what is, dramatically, at least, a damp squib. Nothing is resolved. The only takeaway is that the North American Government and the Mob are working together against the Syndic is some ways, which does not come as much of a revelation, given information which was shared early on in the book.

A couple of plotting elements irked me particularly, but may not trip up other readers. I ended up confused by the sequences in which Charles Orsino initially goes undercover. The way the material was presented, I assumed that his invented identity, Max Wyman, is an actual person, and that Charles has inadvertently been put in great danger by Lee Falcone by being given the identity of Wyman, since both Wyman and Charles would be joining the North American Navy at about the same time. I kept waiting for “the real Max Wyman” to make another appearance in the book and precipitate a crisis for Charles and Lee. What happened is that I missed a one-sentence tip-off that Wyman is an invented personality; I didn’t discover my mistake until I reached the end of the book and, perturbed by Wyman’s failure to make a second appearance, went back to the chapter where the identity had first been introduced. Then I whacked myself on the forehead and went, “Duh!” Yet then I realized that, had Kornbluth been a little more clear, if he had perhaps arranged his scenes a bit differently, I would have avoided my mistake. The other element which disappointed me was Kornbluth’s killing off of my favorite character, Martha, the adolescent, telepathic “witch,” to little purpose. Martha and her abilities are a bit of a “bridge too far” for the novel, which didn’t need the introduction of an additional (and non-central) fantastical idea like telepathy. But once she was introduced, I very quickly came to like her, and I looked forward to Charles bringing her back to the land of the Syndic, where she might serve a novelistic role similar to that of John the Savage in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. Instead, she gets killed off in a melodramatic and unnecessary fashion. I missed her.

Unfortunately, no quotes from Cyril Kornbluth survive which would indicate what he had thought of his friend Fred Pohl’s strengths and weaknesses as a writer. Early in his career, Pohl was greatly attracted to collaboration, at least when working on novels; the only solo novel he published during Kornbluth’s lifetime was Slave Ship in 1956. However, Drunkard’s Walk, his next solo novel, appeared slightly less than two years after Kornbluth’s untimely death. Given that it was touted as a satirical science fiction novel in the vein of The Space Merchants and that it is better remembered than Slave Ship, let’s take a look at this book and compare its virtues and shortcomings with those of The Syndic.

Drunkard’s Walk was originally serialized in a shorter form in Galaxy Science Fiction in 1960. Pohl’s novel has the feel of a typical late-1950s Galaxy story: a surface urbanity and wit, many clever turns of plot, and characterization about as deep as that found in a Twilight Zone episode of the same era. The novel-length Drunkard’s Walk, although not a long book, suffers some from excess padding glued to its flanks during the effort to expand it from a novella to a novel; many of the chapters told from the vantage point of a supporting character, Master Carl, feel tacked on and unnecessary. The primary problem faced by the protagonist, Master Cornut, a mathematics professor at an unnamed University, is both original and compelling—during periods of partial consciousness, such as when he is on the verge of falling asleep, has just woken up, or is distracted by the progress of one of his own lectures, Cornut is plagued by an autonomous compulsion to commit suicide, despite being a happy, privileged, and well-adjusted individual. He is forced to rely upon the watchfulness of those who live adjacent to his on-campus living quarters, initially students and later his student wife, to keep himself from slitting his own throat or hurling himself over the railing of his apartment’s balcony. Where the plot ultimately heads is less fresh, at least from the present vantage point of an additional half-century of science fiction stories and films, involving as it does the trope of a conspiracy of secret immortals who seek to wipe out potential rivals before those rivals can realize their own power.

For today’s reader, the primary draw of Drunkard’s Walk may be its setting, the University where Master Cornut teaches. Pohl paints the University as a refuge from the overcrowded, tumultuous outside world, where a sizable portion of the American lower middle class is forced to live on “texases,” off-shore platforms originally constructed as early-warning radar installations, which are now used for dirty jobs such as manufacturing and raw materials processing (each texas produces its own power from the wave energy that crashes continuously against its support legs). Pohl is very skillful at extrapolating a future society and delineating its most colorful details; the future world of Drunkard’s Walk is as colorfully described as that of The Space Merchants. Pohl places the University’s professors, or Masters, at the top of his social pecking order. Masters may take advantage of a sort of droit de seigneur regarding the University’s students. Conjugal relations between professors and students are encouraged, being viewed as beneficial to each, and what are called “term marriages” are common, which may last (presumably on the Master’s prerogative) as briefly as a few weeks. There is a strict separation between Town and Gown, with the latter acting in many ways as a sort of hereditary landed aristocracy, but one which sometimes opts to absorb very talented members of the former into its ranks (as scholarship students). The book’s most accurate prediction is Pohl’s envisioning of distance learning; each professor’s lectures are taped and broadcast, reaching audiences of millions, those who either aspire to degrees of higher learning or who desire access to knowledge.

With Drunkard’s Walk, Pohl showed off his mastery of the clever turns of plot possible within the bounds of a science fiction novel. As a writer of science fiction novels myself, several times while I was reading the book, I found myself stepping back in admiration and doffing my metaphorical hat to Pohl’s skill and cleverness in twisting his plot. (Skip the remainder of this paragraph if you wish to avoid a major spoiler.) The resolution and climax of the novel revolve around the notion that a small group of telepathic human immortals has been secretly manipulating history and society to benefit themselves and to remove potential threats to their hidden dominance. It turns out that Master Cornut is one such threat, as, unknown to himself, he is a potential telepath. His unmotivated suicide attempts are actually the result of telepathic suggestions beamed at him by the immortals on campus, who wish him to remove himself. Even more clever is the immortals’ plot to winnow down the burgeoning population of non-immortals (the world of Drunkard’s Walk is just as overpopulated as that of Harry Harrison’s Make Room! Make Room!). Using their telepathic abilities, they erase all memories from the human race of small pox and how to make a vaccine, saving that knowledge for themselves only. Then, in their roles as heads of Master Cornut’s University, they organize a sociological expedition to a South Pacific island where descendants of soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army have formed a primitive, militaristic tribal society, hidden in the jungle since the end of the Second World War. All of the members of this tribe have been exposed to small pox, which has been eradicated (and then forgotten) in the world outside the island. The immortals take members of the tribe on a lecture tour all over the globe, encouraging them to spread small pox throughout every population they come into contact with by selling their ancient uniforms and flags as souvenirs and by sharing a pipe of peace – reflections, of course, of how small pox was spread through the Native American population by European settlers. They succeed in starting an epidemic, which only Master Cornut’s intervention is able to halt, although only after millions of people have died.

I would argue that Drunkard’s Walk is more skillfully plotted than The Syndic, and its future world is more fully extrapolated. Where does the book fall down in comparison with Kornbluth’s novel? Primarily in the area of characterization, I’d say. Many of the two books’ characters can be viewed as counterparts, and in each comparison, Kornbluth’s characters feel more rounded and fully realized than Pohl’s characters. As a young hero-protagonist, Kornbluth’s Charles Orsino is more appealing, magnetic, and interesting than Pohl’s rather bland Master Cornut. In the role of elder advisor and provider of knowledge, Uncle Frank is much more intriguing than Master Carl, who comes across as a self-involved old bore. Similarly, Charles’ romantic interest, Lee Falcone, is far more three-dimensional than Master Cornut’s student-wife, Locille (although Locille has her appealing qualities, too). There is less differentiation between the quality of characterization of the two novels’ villains, although there again I would give the edge to Kornbluth’s villains (Pohl’s lean a bit too much toward the mustache-twisting variety).

Although Drunkard’s Walk was marketed as a satirical comedy – the blurb on the original Ballantine Books paperback edition reads, “Not since The Space Merchants — an S.F. novel so biting funny, so sharply satirical” – I found that the book’s humor fell flat. Unlike the humor found in The Syndic, which has held up well, the gibes in Drunkard’s Walk feel dated and forced. Also, although Pohl’s novel ends in a paramilitary assault on the immortals’ stronghold, his book contains no action scenes nearly as gripping or as richly portrayed as the battle scene Kornbluth set in rural Ireland.

What can we discern from this comparison of The Syndic and Drunkard’s Walk? Regarding the relative contributions of Frederik Pohl and Cyril Kornbluth to their shared novels, I would venture to say that much of the credit for those novels’ plotting, world building, and social extrapolation should probably be given to Pohl. However, I suspect that a goodly portion of those books’ rich characterizations (especially in contrast to the sketchy, minimal characterization found in so many of their contemporaries), their humor, their physical descriptions of settings, and their action sequences can be chalked up to Kornbluth’s input.

At this point, only Fred Pohl could say for certain. And considering the more than half-century that separates those novels’ composition from the present day, even he might have difficulty sorting out who contributed what.